There is a space between history and mythology where stories sing…

The air was muggy. It had rained in the early evening when dusk kissed darkness and the stars came out to play hide and seek. The scent of fresh mud permeated the air along with the silt that slid through the gaps of her toes. It was cool, sliding over the skin despite the humidity. Now standing under the starry sky the darkness was so thick it threatened to consume those who stood at the banks of the river Matla. One could almost swallow it, wondering if the stars would burn the gullet as they trickled down the throat. The boat was readied under the canopy of trees and foliage, dark clouds floating across the sky blocking out the light every few minutes. Clouds that smelt of rain.

It was on a night like this many years ago that the Sun Prince had first found a gift for his younger sister Eenakshi. The Sun Prince had set out in the dark of the night in search of a gift for the Princess’s twelfth birthday. The boat had rocked steadily on the river as a light drizzle of rain wet the Prince’s expensive silk shirt. The Sun Prince sailed on the Matla his translucent shirt clinging to his wet skin, his khukuri drawn and ready. He had been given many ideas for the Princess’s gift but none had truly struck a chord. There was a bracelet of rosy pearls with a clasp made of gold from the southern peninsula, a sari of raw silk from a city in the far east, hidden in the desert. Baskets of fruit and sweetmeats. The Sun Prince had bought all of these and yet none had been enough. And so in the dark of the night when the stars sparkled bright enough to burn he had set sail.

It had not taken long before he stopped, his eyes catching on a glint of gold and amber in the midst of leaves and darkness. The hair of his neck stood on edge and goosebumps trailed up his slick skin. He was so still that even the soft lull of the river and the fall of the rain stopped for a second as the tiger unfurled itself. It was a gigantic beast, amber and obsidian fur glinting in the same starlight that illuminated the iridescent scales of the fish that swam in the Matla. The gold eyes roamed over the Sun Prince, the tiger’s dark nose twitched in trepidation. It was like a well-choreographed dance, each warrior waiting for the other to make the first move. The Sun Prince watched the tiger, refusing to acknowledge the fear creeping through his lungs and infused in his breath. But the elements could only stay still so long and finally, the tide was pulled into motion by the moon and the boat began to move. The tiger snarled, a black lip curling over a fanged tooth, before it lunged.

The tigers in the Sundarbans were revered by the King and his children. Yet as the Sun Prince dove into the silty waters of the Matla to avoid being torn into shreds he raised his khukuri in an arc that caught the magnificent animal in the belly. It gurgled softly in pain as dark blood seeped into the wooden planks. The Prince rose from the banks his khukuri washing away with the river, clambering onto the boat that the injured tiger now lay on. His own cheek held a gash from where the tiger’s claw tore into his skin. It was an elderly beast the Sun Prince noted as it laid its head on his lap ignoring the blood that seeped into his pajamas. Guilt had eaten at him as he watched the labored breathing of the beast, its bristling fur soft against his skin. The Sun Prince knelt his head to the tiger’s fuzzy ear, whispering his apology. The tiger’s gold eyes looked towards him, the prince’s dark hair swept against his head, his eyes filled with tears. It studied the prince before one feeble paw lifted and touched the Sun Prince’s damp cheek, his blood staining the rough underside of the tiger’s paw. Almost like absolution, forgiveness.

The boat moved slower now even as the rain came down with more force. The added weight of the tiger’s body, slowing its journey through the Matla. The Sun Prince let his salty tears fall onto the fur of the tiger as he prayed for its journey through the heavens. When he finished he let the tiger’s body drift down the Matla and make its journey onwards. It was then that he heard it. A soft mewling sound. The Sun Prince froze, now defenseless, wounded and tired from grieving the tiger he had never meant to kill, he didn’t think he would be able to sustain another battle that night in the mangroves. But no danger came through the dense foliage. Instead, the cries the Prince heard were more despondent and persistent than the rain that beat into the ground.

The Sun Prince dove back into the river, swimming towards the bank. It took him time to navigate through the dense forest until finally, he pulled aside a curtain of vines near the same spot he had seen the glint of amber and obsidian. There in front of him lay a tiny tiger cub. His whimpers and mewls drowned out all other noise. The Sun Prince couldn’t help but approach the cub, no larger than a small dog. He held out his fingers tentatively towards the cub and watched as it neared him in cautious trepidation. It took much time before the cub finally deemed the Sun Prince to not be a threat and let his fuzzy skull brush the Prince’s wet hand.

The next day with his wound still bleeding the Sun Prince set down the cub in front of Eenakshi along with a bracelet of rose gold pearls, a formal silk sari, baskets of khajoor and plates of sondesh. The tiger was said to have been promptly placed in the young girl’s lap, his muddy pawprints staining the eggshell-colored sari she wore, his little teeth nipping at her ear, licking away the blood that bloomed there. But since that morning when the darkness was swallowed by the pale-colored dawn, Eenakshi’s name was forgotten and she was known henceforth as the Tiger Princess.

***

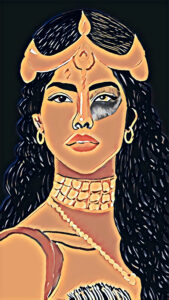

No one had seen the Tiger Princess outside of the stone-walled grounds of the palace in the years since she received the gift. Yet there were rumors that floated through the kingdom about her. Her legendary beauty was the most famous. She was said to have eyes that were darker than the night and that held the stars, eyelashes so long they had to be trimmed with thin gold scissors. Her ebony hair was softer than the wings of the doves reared in the palace, her lips were said to be darker than the fruit of the date palm trees and her skin the color of gold honey illuminated by sunlight. They said that golden bindi worn between her eyebrows was melted gold that the king had poured into the indents of her skin when she was born. They said that when she sang the clouds parted so the moon could illuminate the dark forests and when she danced the earth sprouted tiger lilies. They said that her tiger, Khan, was served the blood of the prisoners held in the stone-walled castle and that he was taught to guard her, trained by warriors that had sailed all the way from the foreign lands of Africa.

There is a mystery and an air of secrecy that surrounds the unknown. So it was with the Tiger Princess. Some said she had sailed away on a boat made of oyster shells with her beast. Others claimed that she reared her cub to be so fearsome that the King had locked both away in one of the turrets of the stone fortress. But no one knew the truth. No one knew where the Tiger Princess was or what she truly looked like.

Eenakshi for her part was tired. She was tired of being told that she was to never be seen so she might fetch a most advantageous alliance from a prince who would one day marry her. She was tired of the grey stone walls, she was tired of the humid air, she was tired of not seeing the world, but most of all she was tired of sondesh. Once her favourite dessert in the world, she now hated the saccharine taste of the white dessert and the squelch of it between her teeth. Sleeping deeply through the days, the shadowy slivers of her room that weren’t illuminated by sunlight would be inhabited by Khan, now an enormous beast. His tongue lolling out of his open jaw, his fur glistening and sleek, brushed every day with a mother-of-pearl hairbrush. The rumors around Khan’s ferocity were greatly false, he was the most docile beast imaginable, though he did drink a bowl of lamb blood every morning to strengthen his bones. He kept his Princess company, wherever she went he followed. He would sleep when she slept, eat alongside her and when the Queen came every morning to wake Eenakshi with a golden plate filled with holy offerings he would wait patiently as the aarti was conducted. Three round circles around his face, a vermillion streak painted between his eyes and a sputtering cough as the sondesh was placed between his sharp teeth. Khan, was not a fan of sondesh either. Once the sweet had been consumed, both tiger and princess would fall back into a deep slumber until the stars shone. When the rest of the kingdom slept the Tiger Princess would exit the stone walls of the palace and head into the forest towards the Matla, her tiger following her stealthily his fur glowing under the starlight.

Eenakshi had been sneaking out for many moons. Her dark hair glistened, bound into a bun surrounded by fragrant flowers and she wore the red sari her brother had gifted her alongside Khan. The sari was tied in a way that it hung just above her knees, her legs were muscular and held many scars from practicing warcraft. While the royals tried to keep Eenakshi confined, to add to her mystique and draw in the strongest and most prosperous princes and kings from the neighboring kingdoms she had long since found ways out of this lifestyle.

She had been trained in the art of battle by the Sun Prince for many years. Twice a week under the moonlight they would train with khukhuris until Eenakshi could beat him in a fight. It had started that way. The Sun Prince would wait for Eenakshi to climb down the vine and they would walk to the Matla, tossing Khan fresh khajur to eat as they went. There on the same boat on which the Sun Prince once carried Khan home, he and Eenakshi would battle. She would wrap the sari between her legs and tie a cloth around her breasts until she could defeat the prince. But long after these lessons had come to a close, Eenakshi chose to sail on the Matla. Night after night, underneath the canopy of the Sundari trees she would sail on the river. Her long hair would unravel from its bun and trail into the river until it touched the silt below, she would lie on the dampened wood planks of the boat, her cheek skimming the cool water, her slender legs braced on Khan’s sturdy back. There was freedom in these nightly boat rides, freedom that was missing in cool stone walls and mouthfuls of sondesh.

These nightly sailing expeditions were mundane adventures. Often times Eenakshi would practice her footwork, two khukuris clasped in her hands, she would dance around Khan and fight off invisible attackers, ducking and rolling, lunging and jumping. Other times she would simply let her fingers skim the water, she would let her hair unravel, the rain dampen it and then she would pick lotus blossoms from the water, braiding them into her hair. On some nights she found injured turtles, which she would hide in the pallu of her sari to heal at home, before coming back to release them in their natural habitat. Sometimes she would count the stars amidst the canopy of Sundari trees and she would dream. Her hand would drift to the tear in her left earlobe, a love bite from Khan the first time he met her and she would imagine a life for him and herself outside of the stone-walled fortress and the kingdom hidden in the Sundarbans. She dreamt of wandering the world in a desert caravan, of watching the priestesses in the south perform their holy dances, of tasting saffron and salted tea in the rugged hills of Kashmir. But she was the Tiger Princess and no matter how far she sailed on the Matla, the shackles that bound her to the palace pulled her back before dawn.

The air was muggy that night. It had rained in the early evening when dusk kissed darkness. The scent of fresh mud permeated the air along with the silt that slid through the gaps of Eenakshi’s toes. It was cool, sliding over the skin despite the humidity. Now standing under the starry sky the darkness was so thick it threatened to consume her. She could almost swallow it, wondering if the stars would burn the gullet as they trickled down her throat. Her boat was readied under the canopy of Sundari trees and foliage, dark clouds floating across the sky blocking out the light every few minutes. Clouds that smelt of rain. Despite the dense cover of clouds, the moon shone through and Eenakshi sat at the stern of the boat her toe dipped into the water letting ripples trail behind them as she set sail with Khan. He peered into the water, his tongue hanging out of his mouth as though he intended to swallow the monsoon, the stars and the darkness all at once.

Silence was a language they were well-versed with. It brought comfort to hear each other’s breath amidst the tickling breeze and the rustle of the leaves on the Sundari trees. But halfway through their journey as the waters deepened and the silty bottom disappeared from visibility, Eenakshi let out a stern command as Khan swiped his paw through the water as he sometimes did upon seeing one of the iridescent fish of the Matla.

“We do not eat the fish,” she told him sternly, watching his expression turn dejected and sad as he retracted his large claws from the slippery water. The boat shuddered to a halt as his paw rested on the wood again, burying his face under the tangle of Eenakshi’s scarlet sari in shame.

Eenakshi looked around puzzled at the sudden hindrance. She stood, tightening the muscles of her abdomen so she wouldn’t fall off the lilting surface of the boat. She looked around to see whether it was a stray log or if the boat had gotten stuck in a bank of silt. But it was the mewling sounds emitted by Khan that made Eenakshi look to the forefront of the boat. She grumbled before she turned to see what had troubled her beast, the fearsome tiger rumored to drink criminal blood. But even her eyes widened in terror as the creature slithered onto her boat. Khan all but clambered into her lap, his wet nose quivering in between the curve of her neck and shoulder, he curled his body as tightly as he possibly could and still, he did not fit in Eenakshi’s lap. The creature was the oddest thing Eenakshi had ever seen. With the enormous head of a crocodile, his gold and green scales shone in the dark. And it had the supple sleek body of a fish with mottled scales of indigo and emerald. Despite the heaviness of the creature’s frame it moved with sleek haste and grace as its skull rested on the boat in an almost imperious manner.

“Tiger Princess,” the creature greeted in a rumbly voice like the sound of water rushing over rocks.

Eenakshi could only watch, her hands fisted in Khan’s fur as his enormous body quivered in her arms.

“I am Makara, embodiment of the rivers, protector of the Matla,” he said, his tongue swiping over his fangs as he spoke.

“The Goddess of the Mangroves wishes to reward you. For protecting our fish and turtles, for raising our orphaned cub and for your continued respectful use of the forest.” the Makara continued, “I will pull your boat to the sacred grotto.” he said without waiting for Eenakshi’s response. His body slithered off the boat and the wooden vessel began to sail again, faster and more agile than before. For once the warrior princess was stunned into silent agreement as Khan watched the path the boat carved into the Matla, his nose quivering in fright.

Eenakshi had never wandered so far from the palace before and as they sailed down the river the foliage thinned and the starry skies opened up above her showering her in silver starlight. Looking at the constellations she had only seen in bits and pieces from under tree cover Eenakshi almost forgot that she was being pulled down the racing river by a frightening creature. But not long after the skies opened up the Makara diverted paths and the water became shallow pulling into a secluded cave. Eenakshi stepped out of the boat, the bottom of her sari sodden as she waded deeper into the cave, following the Makara as he slithered deep into the darkness. Her tiger followed her, his whimpers echoing throughout the cave.

Finally in the deepest depth of the grotto, when there was nowhere further to go, the trio stopped. A single hole in the roof of the stone let moonlight stream in, illuminating the large wall in front of them. There on the hewn stone walls of the cave was a carving that was three times Eenakshi’s size. The gold indents in the wall were breathtaking as Eenakshi took in the carving of the woman before her.

“The Goddess, Bonbibi,” the Makara introduced. And as he spoke, there in front of Eenakshi’s eyes the carvings came alive. The grey-green rock turned into supple soft skin, gold and pearls, and strands of dark curling hair. A single eye the color of the darkest ebony, the other the gold of the tiger’s eye surrounded by amber and obsidian fur. The Goddess studied Eenakshi, before her voice boomed through the cave, the sound of hundreds of birds taking flight, the rustle of the Sundari trees, the rush of the rivers and the downpour of the rain encompassed within her strong vocal cords.

“Tiger Princess,” she greeted, before continuing. “I have watched you sneak into my mangrove forests for many years now. Long ago I saved your brother from one of the tigers who roamed in my forest like a mighty king. It was not sheer luck with which he escaped. I gave his khukuri the blessing of aim. And yet I was displeased that another one of your kind had disrupted life within my forests.”

Eenakshi only gaped, Khan hiding between her legs his snout visible through her sari. The Goddess continued despite Eenakshi’s evident speechlessness.

“I expected from you the same disregard I expected from the Sun Prince. And yet every night when you have entered my forest you have defied my expectations. You have reared the orphaned cub from my forests with so much love that he is now nothing but a spoilt kitten,” here her voice hardened with concern, “and it seems, a scared one at that.”

Eenakshi gulped, raising an eyebrow, wondering whether she was being lauded or scolded.

“You have protected the sacred fish of the Matla from the cub’s greedy paw over and over, helped injured turtles, hidden my holy oysters from being poached for the pearls and have kept my mangrove forest clean.” The Goddess loomed over Eenakshi. “And thus, Makara and I have decided to gift you a boon.”

Finally, Eenakshi found her voice. “A boon?” she asked the Goddess.

“Indeed.”

The Goddess beckoned Eenakshi forward with a single finger and Eenakshi found herself pulled forth, until she stood a mere foot away from the gigantic Makara, close enough to see every green and gold scale on his head.

“Inside Makara’s mouth, you will find a single black pearl. This is the Shaligram. It is a holy stone. The Shaligram will give you three nights to wander any single dreamscape of your choice. It can grant you your wish of freedom for three nights. But beware Tiger Princess, it must be used under the full light of the moon and the stars and with each night that you use it, the color will fade until it resembles but a normal pearl. When all the color has leeched from it you must return it to the waters of the Matla where it will find its way back to Makara.”

As the Goddess spoke, the Makara opened its jaw wide, and there at the center of its tongue sat the magnificent black pearl. Eenakshi reached for it tentatively, letting it slide into her palm, smooth and slippery. She looked up at the Goddess, a question in her eyes.

“The boon is rarely gifted,” the Goddess said, her voice fading, “Use it well Tiger Princess. Use it well.”

It was as though Eenakshi blinked and the Goddess had transformed back into the carved rock facade. In front of the carved wall was the most detailed sculpture of a half-crocodile half-fish creature, in grey and gold rock. Eenakshi stared, her arm reaching behind her to soothe and pet the quivering Khan.

The next night when the moon rose in the sky along the iridescent stars, Eenakshi set out on her boat with Khan onto the Matla. She rowed out where the foliage thinned and moonlight cloaked her in a silver glow and clasping the pearl between her palms, Eenakshi wished for one thing only. ‘Magic.’

It happened in a single second, the way breath ebbs from the chest – the scent of the river vanished, the humidity stick to her skin disappeared and Khan’s deep steady breaths went silent. When she opened her eyes she stood on steady ground, the sky above her starless and dark and yet the air was illuminated by glowing candlelight. The sound of the bansuri, the esraj and the dotara permeated the air. The canopies of the marketplace in front of her were deep blue and silver so unlike the red white and gold she was used to but still, Eenakshi noticed none of it. She noticed only one thing, her tiger was gone. She searched through the magical marketplace the Shaligram had conjured, pushing aside a variety of strange creatures shopping through the marketplace. She called his name ignoring the irritated looks she got from passerby’s for disrupting the peaceful string music and silence of the market.

Finally covered in sweat and panting, Eenakshi was close to tears. No matter where she looked and how far she ran she always circled back to the center of the marketplace, yet Khan was nowhere to be seen. She patted at the folds of her deep red sari trying to find the black pearl but that too had disappeared. In a state of complete panic, Eenakshi began to wander aimlessly through the lanes of the market. Finally dejected and unable to understand how her wish had gone so very wrong she sat down on one of the onyx-carved stools of the market, her head pounding into a malignant ache.

“You seem upset,” a melodious noise trilled near her, startling her off her seat with a squeal of surprise.

When Eenakshi looked up her eyes widened as she tried to comprehend what she was looking at. In a magnificent silver cage with a curlicue lock there was an enormous bird with the most exquisite feathers. He was perched on a gently rotund silver swing, enormous black claws curling around the undulating silver log. The plumage on his head in shades of teal, silver, navy and deep indigo. It was the most beautiful peacock Eenakshi had ever seen. The words seemed to stick in her throat as she tried to speak. The large silver eyes studied her quizzically as she studied it.

“Why are you upset?” it cooed again, it’s voice a trill of song and the low rumble of clouds before they burst into a shower of rain.

“What are you?” Eenakshi managed to choke out in response, trying to steady her erratic breathing.

“I am the Mayurpankhi.” the peacock said.

“But you aren’t supposed to be real!” Eenakshi exclaimed in surprise. “My brother told me stories about you when I was a young girl.”

“Before I was captured for a showpiece for this magic marketplace, I was a wondrous creature. I could travel a thousand realms, I could carry a hundred kings on each of my wings and I would see the world.”

The peacock let out a sad sigh. “And now I am stuck here, for many moons I have been stuck here, caged in this penitentiary of silver.”

“What is this?” Eenakshi asked the peacock, gesturing to the enormous canopied stalls around her.

The Mayurpankhi looked astonished. “You don’t know?” he asked in his mottled voice, surprise contorting his large eyes. “This is Bengali Bazaar!” he exclaimed. “This is the most magical realm in all of Bengal!”

Eenakshi looked around noticing the patrons of the bazaar, a gasp catching in her throat as she noticed apsaras and demons and mythical creatures she couldn’t recognize. Hesitance crept into her being as she took it all in. A hesitance tinted with curiosity. “All of this is magical?” she asked the Mayurpankhi. “Indeed!” it boomed. “Much like myself.” it purred, puffing out its enormous feathers before letting out an outraged squawk as the feathers were contained and bent by the confines of the cage.

“Go on then,” it urged her after settling its feathers gently against its body. “Explore, humans rarely get a chance to come here unless they are granted a boon or a wish stone like the Shaligram or Monohor Kanta.”

Eenakshi nodded, moving further into the market, though her thoughts still stuck on Khan. Heading under the first canopy of azure and starry silver cloth she came across a large moustachioed vendor. Atop his table were a number of large Dhokra sculptures, the metal carved into lively figures. Women in saris, a goldfish in a pond of lotuses, there was even a lifelike imitation of the Mayurpankhi.

“The best Dhokra craft in all of Bengal!” the man said his skin glowing with a thin veneer of sweat. “Look,” he said pointing to a woman holding a dotara delicately in her hands. “Gaao Amaar Bhalobasha” the man whispered lovingly to the sculpture and immediately the woman’s tiny metal fingers began working the dotara, her mouth opened in a mechanical manner and a stunning rendition of a Vaishnavi Padavali leaves her mouth. The ancient ballad sung for the God Krishna and his love Radha as they danced a raasleela in the fields of Vrindavan.

But once the song has finished and Eenakshi had seen the singing fish jump in and out of the metallic lotus pond she moved on. The Dhokra vendor looked despondent as she walked away. She walked past reams of silk and wool and shawls made of Kantha embroidery before her eyes caught on a most magnificent piece of silver silk upon which iridescent threads shimmered. The embroidery was the most intricate Eenakshi had ever seen.

“What is this?” she asked the seller, a young woman with mottled blue skin. “This is a Baluchari sari,” she told Eenakshi, a forked black tongue peeking out of the corner of her mouth to lick her lips. “It changes its embroidery every time you will wear it,” the woman said, beckoning her to take a closer look. “See right now, it tells the story of the Mansamangal Kavya. See the lovers Chaitanya and Padmavati, their entire story is embroidered onto the silken fabric.” the woman draped the sari against her bosom and Eenakshi watched in amazement as the embroidery changed into one of the comic tales of Gopal Bhar and his legendary wit. Eenakshi knelt down to whisper to Khan, pointing out what she was seeing and her heart ached when she remembered that in this realm he had disappeared. Tears filled her eyes and she ignored the cries of the sari seller, running through the canopies of blue, trying to compose herself. Finally, she stopped in front of a stall filled with terracotta pottery. The man selling it offered her an empty clay container shaped of red terracotta. It is empty at first and though Eenakshi refused, the vendor persisted until annoyance made her snatch it from his hands. She wiped at the dried tear tracks on her face before she felt the clay cool within her palms. When she looked at it once again she was surprised to see it filled with sondesh, the saccharine fragrance of it overwhelmed her and she remembered how every morning she and Khan try to get rid of the dessert. Her tears resurfaced again as she tried to understand what happened to her beloved tiger. She hardly knows her identity without being the Tiger Princess.

Dejected and tired Eenakshi wandered back towards the Mayurpankhi. It looked at her with sympathy. “Don’t worry,” it cooed at her softly. “Dawn approaches swiftly. You will be able to return home soon.”

There was hope still then, that even without the Shaligram she would be able to return home, return to find Khan.

“Will my tiger be where I left him?” she asks the Mayurpankhi desperately.

“Your tiger?” it asks in confusion. “Did you not arrive here through a wish stone?”

“I used a Shaligram,” Eenakshi tells the magnificent peacock.

“The Shaligram only transports one. Surely your tiger is guarding your body, while your mind roams the realm of Bengali Bazaar. Tell me,” it says, now curious. “Why did you wish to come here? You have been unhappy the entire time.”

Eenakshi sighed. “I was hoping for more.” she confides, watching as the corners of her eyes darken, the market becoming more trasnlucent than real. “I had wanted to roam the mountains of the Afghan, wander the streets of the great emperors, watch the tawaifs of old perform and see the Southern backwaters. I wanted to see the magicians of Dehli and the Fakirs of Lahore.” she raises a finger, pushing it through the gaps of the cage and stroking the Mayurpankhi’s soft feathers. “I wished for magic, because all my life, Khan and I have been mundane. We eat and we sleep, we embroider and we wear silk and leather and we have nothing else. The dawn never brings anything new, anything extraordinary, anything exquisite. For once, I wanted to feel anything but mundane.”

But the Mayurpankhi’s feathers went from soft to nonexistent, as she returned to reality she heard his voice still as he spoke, the voice that reminded her of the song of the nightingale and the rumble of the clouds before rainfall. “Come back tomorrow and I shall give you a present, Tiger Princess.”

When Eenakshi woke, she was overjoyed to see Khan sitting beside her, worriedly nipping at the ends of the sari she wore. Tears filled her eyes, like little pearls as she threw her arms around him, holding him close even as he squirmed and squirreled away in confusion. When she was done ascertaining that he was truly there, smelling his musky fur and clutching his soft ears, he gave her long lick across her torn ear, the jagged edges of which remembered his teeth from many years ago and tingled.

Later, the next night when they returned, Eenakshi’s heart stuttered to leave Khan again. It made her nervous to know he wasn’t behind her, dogging her footsteps, nuzzling her calves at every turn. But she wanted to know what gift the Mayurpankhi wanted to give her. And so despite her fears, she placed her head on Khan’s soft flank, closed her eyes and wished to return to Bengali Bazaar.

As the silt and sticky air disappeared and the canopies of azure and pearly silver appeared, Eenakshi ran straight to the Mayurpankhi. His silver eyes were closed when she approached and his large head ducked under an enormous arm as he snoozed. She waited nervously wondering if she should prod at him, but it was as though he sensed her arrival for his eyes opened lazily and whe he saw Eenakshi he unfurled his large body from the tight coil it was in.

“You came back, Tiger Princess?”

“You asked me to,”

“Yes but I didn’t think you would have the courage to. More so since it seemed like you had lost half of your soul without your tiger.”

“I wanted to know what you had wanted to give me,” Eenakshi told the peacock truthfully.

The Mayurpankhi sighed, “I know too well how it feels to be trapped, Tiger Princess.” I once sailed the sky with kings and queens. Once I saw the entire world. Now I have been stuck, caged like a common parakeet. I have an eternal curse.” In a slow movement, the Mayurpankhi ducked its head once again, gripping one of his enormous feathers in his silver beak he tugged with vicious force and Eenakshi winced as it came away from his body. A drop of dark blood bloomed on the thick tip of the feather. “Here,” it said with a quiver in its voice, extending the feather towards Eenakshi gently.

“If you ask the Baluchari sari weaver to weave these into a pair of slippers for you and your tiger, you will be able to travel the seven seas and the entire world.” The peacock looks at her wistfully. “The way I once did.”

Eenakshi’s eyes watered as she beheld the magnificent peacock feather in her hands. A priceless gift. “But,” she stumbled clearing her throat. “What will this cost me?” she asked finally. “Surely this is not free?”

“Tell the weaver I will pay her tomorrow,” the peacock cleared its throat, “And from you, I would like for you to tell me a story.”

“A story?”

“I have been stuck in this prison for many centuries. I wish to roam the world once again, tell me a story Tiger Princess so I may be free for a single moment.”

The peacock closed its eyes, nestling its enormous feathers against its body, making itself comfortable as Eenakshi began talking. “On a night when the clouds were filled to the brim, ready to burst, The Sun Prince went out on the river Matla in search of a gift for his younger sister…”

The story flowed like the water of the Matla over the muddy banks as Eenakshi recounted how she and Khan came to be together. And when she was done the Mayurpankhi extended his head through the curlicue silvers bars of his cage and nuzzled her cheek gently. The next night when Eenakshi returned to take the peacock slippers, two for her own feet and four for Khan’s paws from the Baluchari weaver, she watched as the weaver showed off her enchanted silver sari to patrons and her eyes caught on the embroidery. There on the silver cloth was a story she was well versed with.

A young prince embarking on a journey on the Matla in search of a gift for his sister, a tiger for a Tiger Princess. The story was now immortal, another folktale for the Baluchari sari’s, famed in all of Bengal.

When she returned to the Sundarbans, Eenakshi tied the peacock slipper sandals onto Khan’s enormous paws and snuck her own feet into them before slipping the now colorless Shaligram back into the waters of the Matla. No one saw her leave the Sundarbans, but her boat was found drifting on the river, slow and sluggish as though it did not know how to simply float without it’s sailor. But rumors fled through the kingdoms and through the Sundarbans. The Tiger Princess has ridden her tiger all the way to the edge of the world on a pair of enchanted peacock slippers. The Sundari trees grew steadily over the Matla, their canopies are soon so thick and dense that not even the stars could be seen from the river any longer. The stars that once burnt and the moonlight that once illuminated the waters of the Matla had all but disappeared.

Now when the Sundarbans are flocked by visitors and the Matla moves more sluggishly, a darker color – more polluted, the boatsmen tell the tourists of the Tiger Princess. They tell them how she roamed the streams of the Matla with an enormous tiger and one day when the sun rose above the horizon she dragged the disappearing moon behind her away on an adventure. The moon no longer shines on the Matla. The boatsmen say she wandered from Bengal to the ghats of Banaras to the fields of Punjab all the way to the South to see the devadasis dance. And when the story is finished, on the undulating surface of the silty waters, they offer tourists a single piece of sondesh on a leaf painted to resemble tiger stripes.